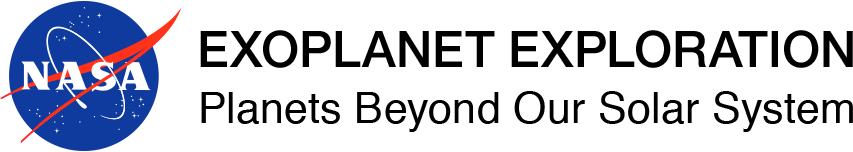

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has found three confirmed exoplanets, or worlds beyond our solar system, in its first three months of observations.

The mission’s sensitive cameras also captured 100 short-lived changes — most of them likely stellar outbursts — in the same region of the sky. They include six supernova explosions whose brightening light was recorded by TESS even before the outbursts were discovered by ground-based telescopes.

The new discoveries show that TESS is delivering on its goal of discovering planets around nearby bright stars. Using ground-based telescopes, astronomers are now conducting follow-up observations on more than 280 TESS exoplanet candidates.

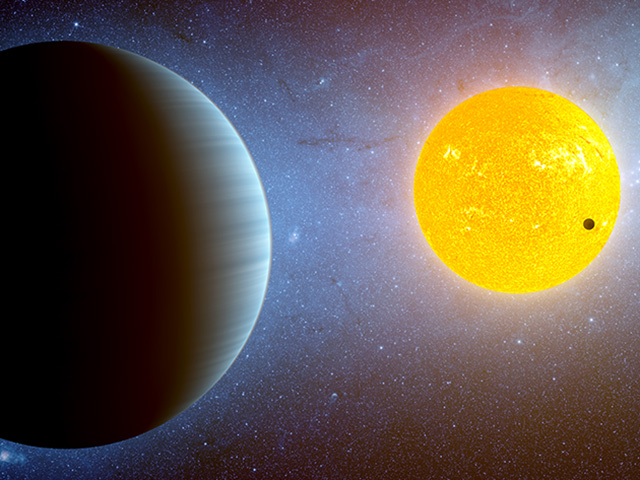

The first confirmed discovery is a world called Pi Mensae c about twice Earth’s size. Every six days, the new planet orbits the star Pi Mensae, located about 60 light-years away and visible to the unaided eye in the southern constellation Mensa. The bright star Pi Mensae is similar to the Sun in mass and size.

“This star was already known to host a planet, called Pi Mensae b, which is about 10 times the mass of Jupiter and follows a long and very eccentric orbit,” said Chelsea Huang, a Juan Carlos Torres Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research (MKI) in Cambridge. “In contrast, the new planet, called Pi Mensae c, has a circular orbit close to the star, and these orbital differences will prove key to understanding how this unusual system formed.”

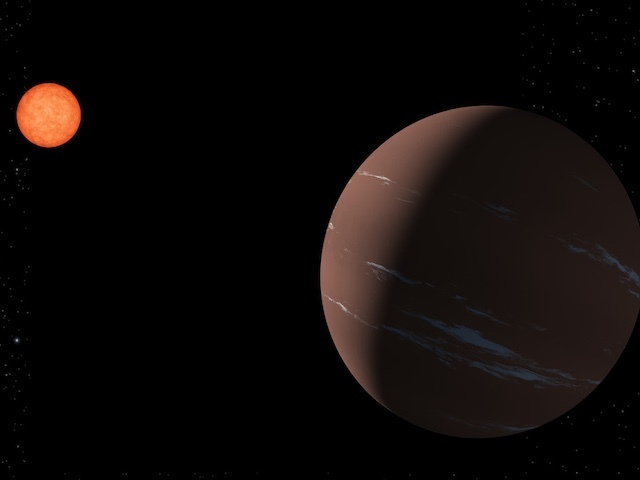

Next is LHS 3844b, a rocky planet about 1.3 times Earth’s size located about 49 light-years away in the constellation Indus, making it among the closest transiting exoplanets known. The star is a cool M-type dwarf star about one-fifth the size of our Sun. Completing an orbit every 11 hours, the planet lies so close to its star that some of its rocky surface on the daytime side may form pools of molten lava.

The third — and possibly fourth — planets orbit HD 21749, a K-type star about 80 percent the Sun’s mass and located 53 light-years away in the southern constellation Reticulum.

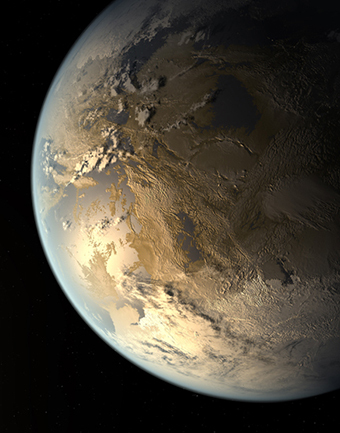

The confirmed planet, HD 21749b, is about three times Earth’s size and 23 times its mass, orbits every 36 days, and has a surface temperature around 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius). “This planet has a greater density than Neptune, but it isn’t rocky. It could be a water planet or have some other type of substantial atmosphere,” explained Diana Dragomir, a Hubble Fellow at MKI and lead author of a paper describing the find. It is the longest-period transiting planet within 100 light-years of the solar system, and it has the coolest surface temperature of a transiting exoplanet around a star brighter than 10th magnitude, or about 25 times fainter than the limit of unaided human vision.

What’s even more exciting are hints the system holds a second candidate planet about the size of Earth that orbits the star every eight days. If confirmed, it could be the smallest TESS planet to date.

TESS’s four cameras, designed and built by MKI and MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory in Lexington, Massachusetts, spend nearly a month monitoring each observing sector, a single swath of the sky measuring 24 by 96 degrees. The primary aim is to look for exoplanet transits, which occur when a planet passes in front of its host star as viewed from TESS’s perspective. This causes a regular dip in the measured brightness of the star that signals a planet’s presence.

In its primary two-year mission, TESS will observe nearly the whole sky, providing a rich catalog of worlds around nearby stars. Their proximity to Earth will enable detailed characterization of the planets through follow-up observations from space- and ground-based telescopes.

But in its month-long stare into each sector, TESS records many additional phenomena, including comets, asteroids, flare stars, eclipsing binaries, white dwarf stars and supernovae, resulting in an astronomical treasure trove.

In the first TESS sector alone, observed between July 25 and Aug. 22, 2018, the mission caught dozens of short-lived, or transient, events, including images of six supernovae in distant galaxies that were later seen by ground-based telescopes.

“Some of the most interesting science occurs in the early days of a supernova, which has been very difficult to observe before TESS,” said Michael Fausnaugh, a TESS researcher at MKI. “NASA’s Kepler space telescope caught six of these events as they brightened during its first four years of operations. TESS found as many in its first month.”

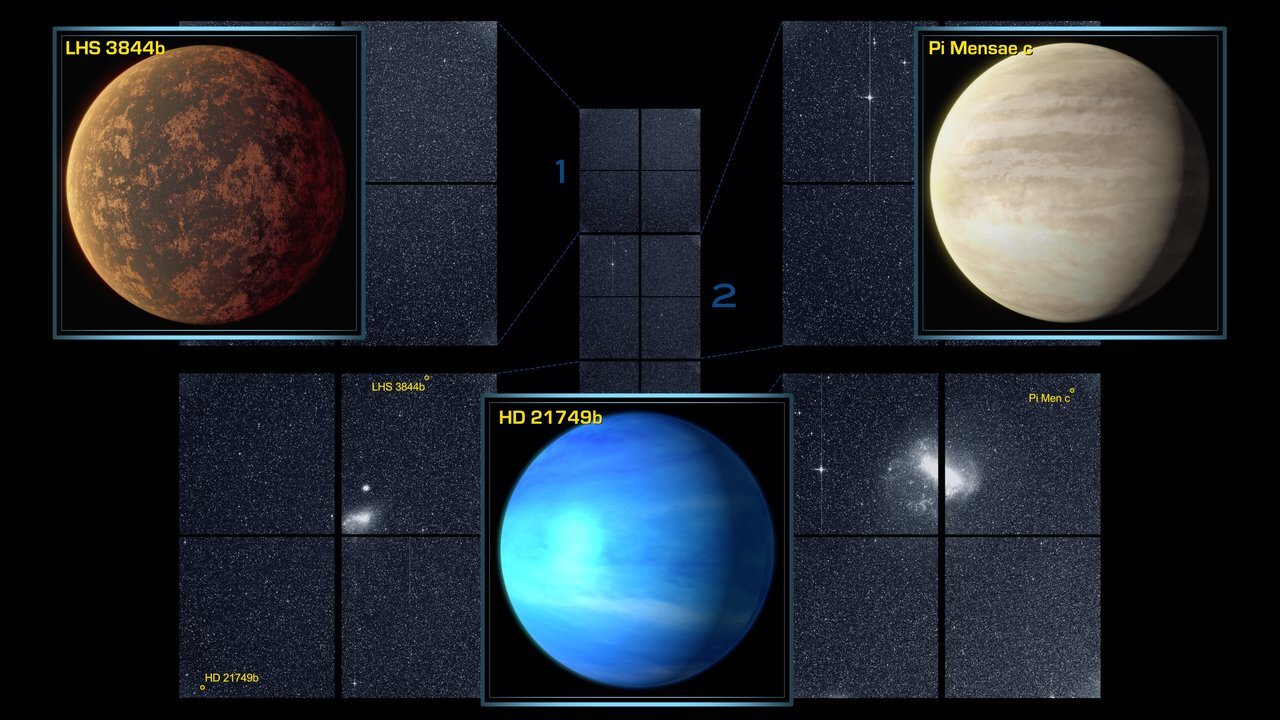

These early observations hold the key to understanding a class of supernovae that serve as an important yardstick for cosmological studies. Type Ia supernovae form through two channels. One involves the merger of two orbiting white dwarfs, compact remnants of stars like the Sun. The other occurs in systems where a white dwarf draws gas from a normal star, gradually gaining mass until it becomes unstable and explodes. Astronomers don’t know which scenario is more common, but TESS could detect modifications to the early light of the explosion caused by the presence of a stellar companion.

All science data from the first two TESS observation sectors were recently released to the scientific community through the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

More than a million TESS images were downloaded from MAST in the first few days,” said Thomas Barclay, a TESS researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “The astronomical community’s reaction to the early data release showed us that the world is ready to jump in and add to the mission’s scientific bounty.

George Ricker, the mission’s principal investigator at MKI, said that TESS’s cameras and spacecraft were performing superbly. “We’re only halfway through TESS’s first year of operations, and the data floodgates are just beginning to open,” he said. “When the full set of observations of more than 300 million stars and galaxies collected in the two-year prime mission are scrutinized by astronomers worldwide, TESS may well have discovered as many as 10,000 planets, in addition to hundreds of supernovae and other explosive stellar and extragalactic transients.”

TESS is a NASA Astrophysics Explorer mission led and operated by MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Additional partners include Northrop Grumman, based in Falls Church, Virginia; NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley; the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts; MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory; and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. More than a dozen universities, research institutes and observatories worldwide are participants in the mission.

Media contact:

Elizabeth Landau

NASA Headquarters, Washington

(818) 359-3241