Fast facts: Are we alone in the universe?

So far, the only life we know of is right here on our planet Earth. But we’re looking.

The big question – Is there life beyond Earth? – comes with an ironic asterisk: we don't really have a universally accepted definition of life itself. That said, we might not need one. We need only detect the telltale signs of life in an exoplanet atmosphere, and we have a better understanding of what those look like here on Earth.

Will we know life when we see it?

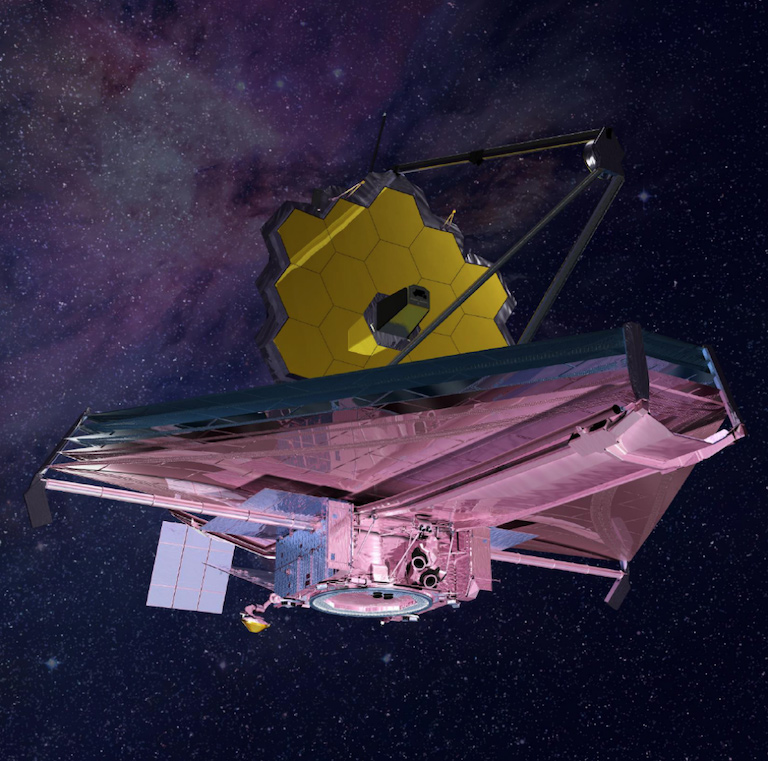

The James Webb Space Telescope, launched in 2021, could get the first glimpses: the mix of gases in the atmospheres of Earth-sized exoplanets. Webb, or a similar spacecraft in the future, could pick up signs of an atmosphere like our own – oxygen, carbon dioxide, methane. A strong indication of possible life. Future telescopes might even pick up signs of photosynthesis – the transformation of light into chemical energy by plants – or even gases or molecules suggesting the presence of animal life. Intelligent, technological life might create atmospheric pollution, as it does on our planet, also detectable from afar. Of course, the best we might be able to manage is an estimate of probability. Still, an exoplanet with, say, a 95 percent probability of life would be a game changer of historic proportions.

How will we find life?

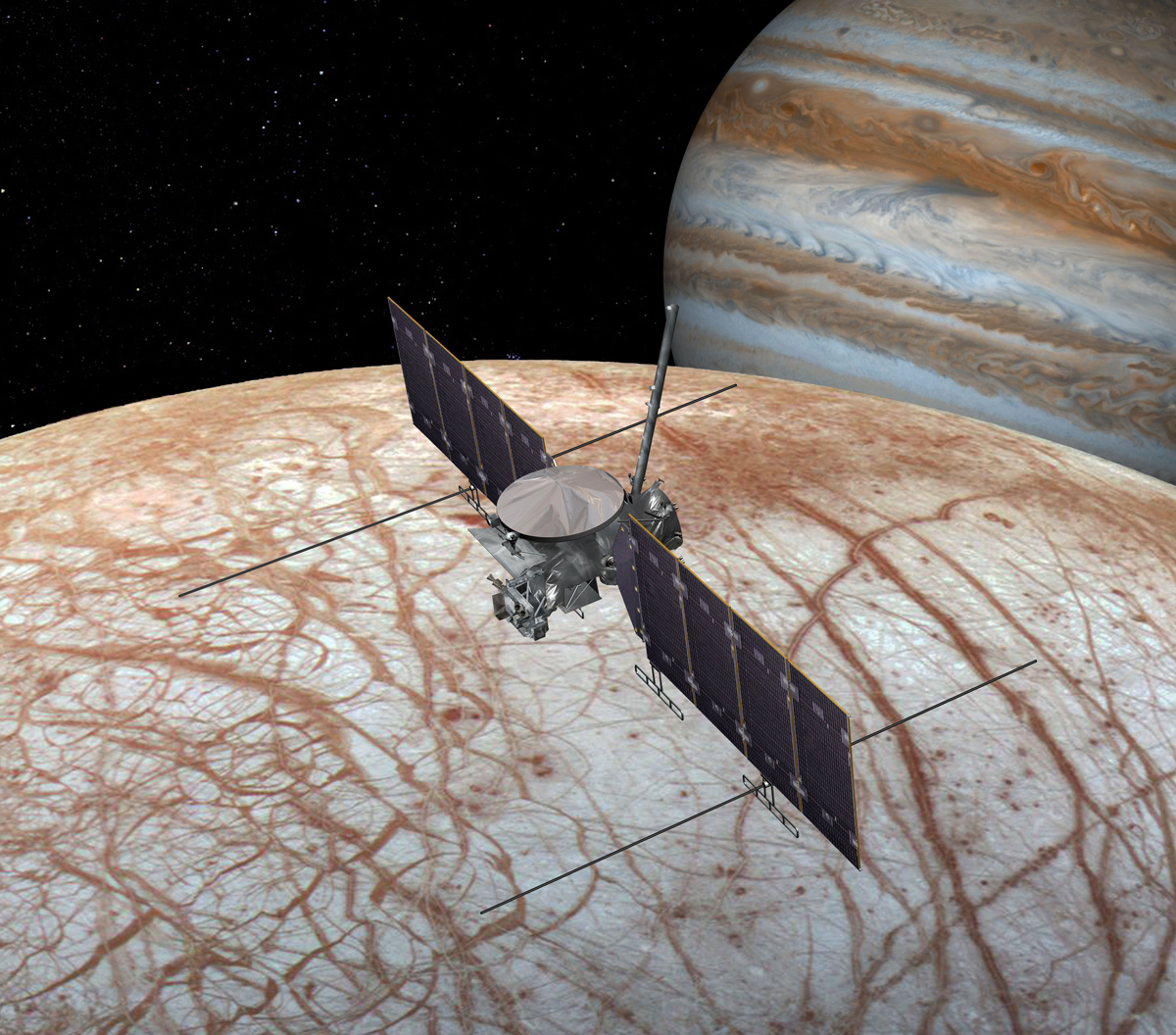

Life might turn up in our own neighborhood: beneath the Martian surface, perhaps, or in the dark, subsurface oceans of Jupiter's moon, Europa. Or maybe the dream of the ages will come true, and we'll eavesdrop on the communications of extraterrestrial civilizations. We might even capture evidence of "technosignatures," or traces of technology (think smog). Barring these strokes of luck, however, the job will be much harder. Light will be the key – light from the atmospheres of exoplanets, split up into a rainbow spectrum that we can read like a bar code. This method, called transit spectroscopy, would provide a menu of gases and chemicals in the skies of these worlds, including those linked to life.

Life as we don't know it

They dwell in the caustic chemical pools of Yellowstone National Park, in the dry valleys of Antarctica, in superheated vents on the ocean floor, and they belong to branches of life that split from our own billions of years ago. "Extremophiles" are life forms that love extreme environments, thriving in conditions that would kill anything else. They might also be analogs for strange life on distant worlds.

Where should we look?

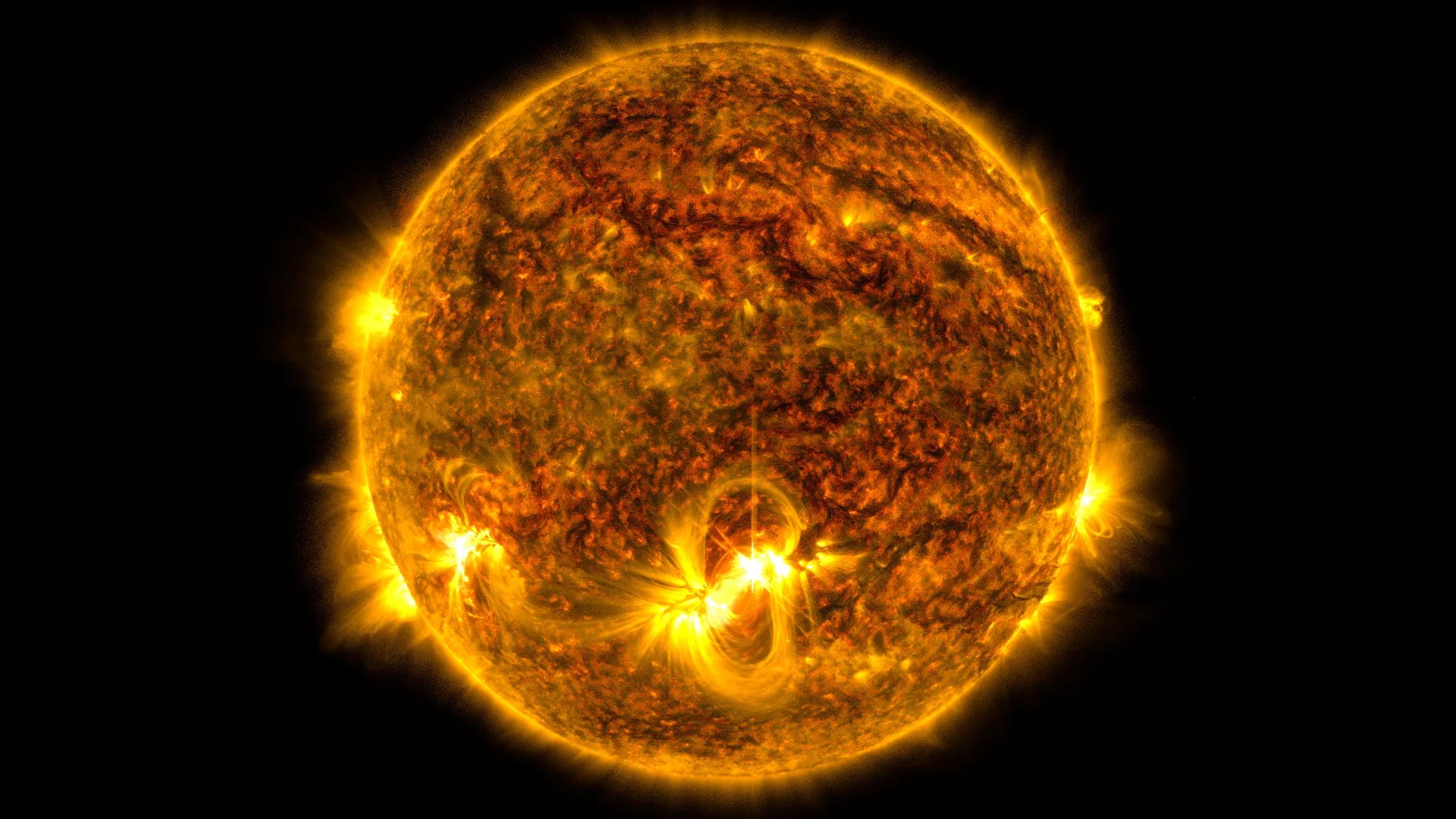

More than 4,900 exoplanets – planets around other stars – have been confirmed to exist in our galaxy, but likely number in the trillions. One of the best tools scientists have to begin narrowing the search for habitable worlds is a concept known as the “habitable zone.” It’s the orbital distance from a star where temperatures would potentially allow liquid water to form on a planet’s surface. Many other conditions also would be required: a planet of suitable size with a suitable atmosphere, and a stable star not prone to erupting in sterilizing flares. The habitable zone is really just a way to make the first cut, and zero in on the planets with the best chance of possessing habitable conditions.

More: How NASA's Astrobiology Program is looking for life in our solar system and beyond.