News | May 23, 2016

NASA finds clues to the birth of supermassive black holes

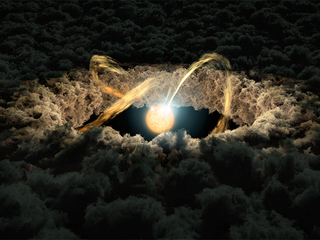

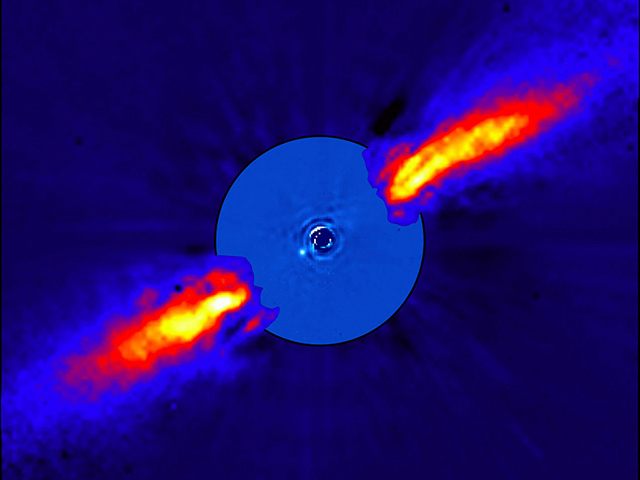

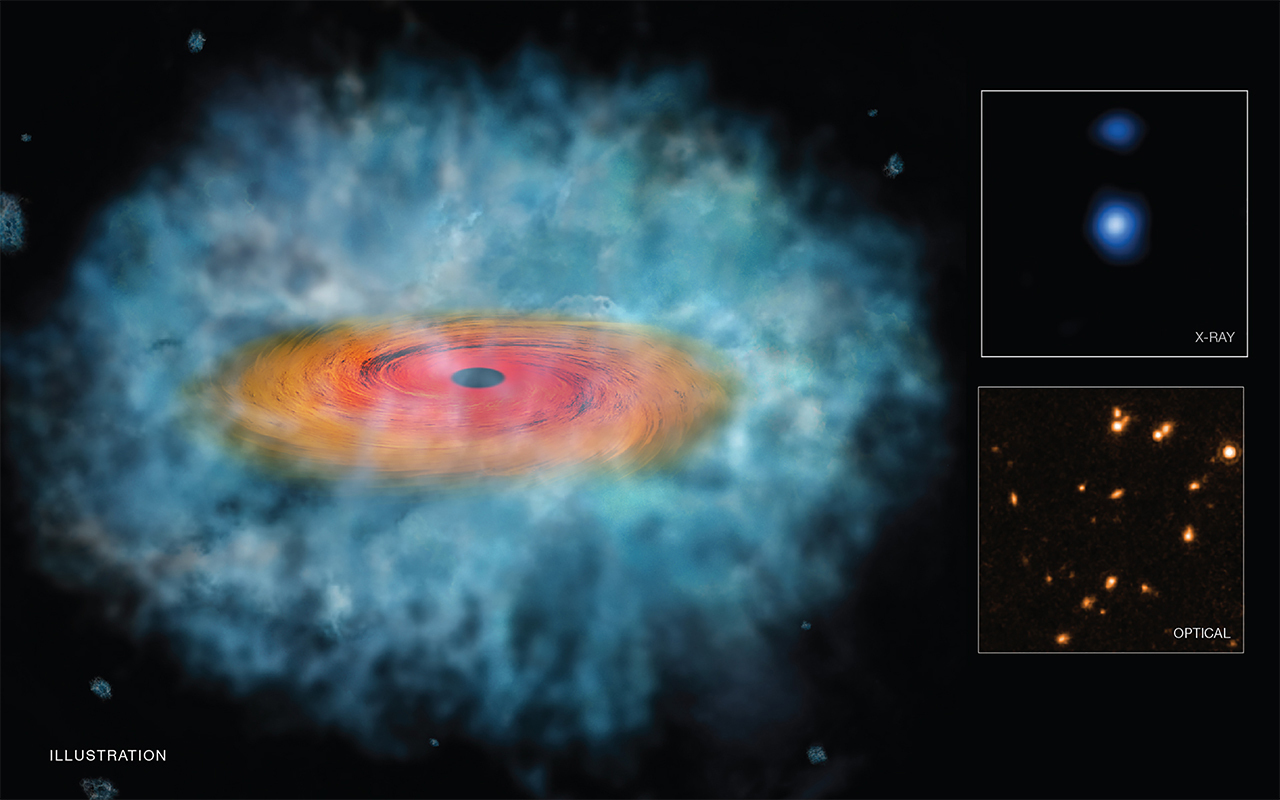

This illustration depicts a possible "seed" for the formation of a supermassive black hole. The inset boxes at right contain Chandra (top) and Hubble (bottom) images of one of two candidate seeds, where the properties in the data matched those predicted by sophisticated models. Credit: NASA/CXC/M. Weiss

Using data from NASA's Great Observatories, astronomers have found the best evidence yet for cosmic seeds in the early universe that should grow into supermassive black holes.

Researchers combined data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, Hubble Space Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope to identify these possible black hole seeds. They discuss their findings in a paper that will appear in an upcoming issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

"Our discovery, if confirmed, explains how these monster black holes were born," said Fabio Pacucci of Scuola Normale Superiore (SNS) in Pisa, Italy, who led the study. "We found evidence that supermassive black hole seeds can form directly from the collapse of a giant gas cloud, skipping any intermediate steps."

Scientists believe a supermassive black hole lies in the center of nearly all large galaxies, including our own Milky Way. They have found that some of these supermassive black holes, which contain millions or even billions of times the mass of the sun, formed less than a billion years after the start of the universe in the Big Bang.

One theory suggests black hole seeds were built up by pulling in gas from their surroundings and by mergers of smaller black holes, a process that should take much longer than found for these quickly forming black holes.

These new findings suggest instead that some of the first black holes formed directly when a cloud of gas collapsed, bypassing any other intermediate phases, such as the formation and subsequent destruction of a massive star.

"There is a lot of controversy over which path these black holes take," said co-author Andrea Ferrara, also of SNS. "Our work suggests we are narrowing in on an answer, where the black holes start big and grow at the normal rate, rather than starting small and growing at a very fast rate."

The researchers used computer models of black hole seeds combined with a new method to select candidates for these objects from long-exposure images from Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer.

The team found two strong candidates for black hole seeds. Both of these matched the theoretical profile in the infrared data, including being very red objects, and they also emit X-rays detected with Chandra. Estimates of their distance suggest they may have been formed when the universe was less than a billion years old

"Black hole seeds are extremely hard to find and confirming their detection is very difficult," said Andrea Grazian, a co-author from the National Institute for Astrophysics in Italy. "However, we think our research has uncovered the two best candidates to date."

The team plans to obtain further observations in X-rays and infrared to check whether these objects have more of the properties expected for black hole seeds. Upcoming observatories, such as NASA's James Webb Space Telescope and the European Extremely Large Telescope, will aid in future studies by detecting the light from more distant and smaller black holes. Scientists currently are building the theoretical framework needed to interpret the upcoming data, with the aim of finding the first black holes in the universe.

"As scientists, we cannot say at this point that our model is 'the one'," said Pacucci. "What we really believe is that our model is able to reproduce the observations without requiring unreasonable assumptions."

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program while the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra's science and flight operations.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, manages the Spitzer Space Telescope mission, whose science operations are conducted at the Spitzer Science Center. Spacecraft operations are based at Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company, Littleton, Colorado.

For more on NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, visit:

For more on NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, visit:

For more on NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, visit:

Media contacts:

Preston Dyches

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-7013

preston.dyches@jpl.nasa.gov

Felicia Chou / Sean Potter

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-0257 / 1536

felicia.chou@nasa.gov / sean.potter@nasa.gov