4 min read

Exoplanets transform our view of the galaxy — and ourselves

by Pat Brennan

Look deeply enough into the night sky, and you’ll soon see how radically the universe has changed.

You might have to borrow some space-based spyglasses - NASA’s Kepler, Spitzer or Hubble space telescopes - to peer into the cosmic depths and watch the faint shadows of planets cross the faces of their stars. Or measure the stars’ wobble, the gravitational tugs of orbiting planets. But as your eyes adjust, the new reality becomes crystal clear. For the first time since we began huddling around campfires, weaving scattered stars into pictures and stories, we know with certainty that we belong to a galaxy packed with neighboring worlds – whole systems of stars and planets far beyond, and vastly different from, our own solar system.

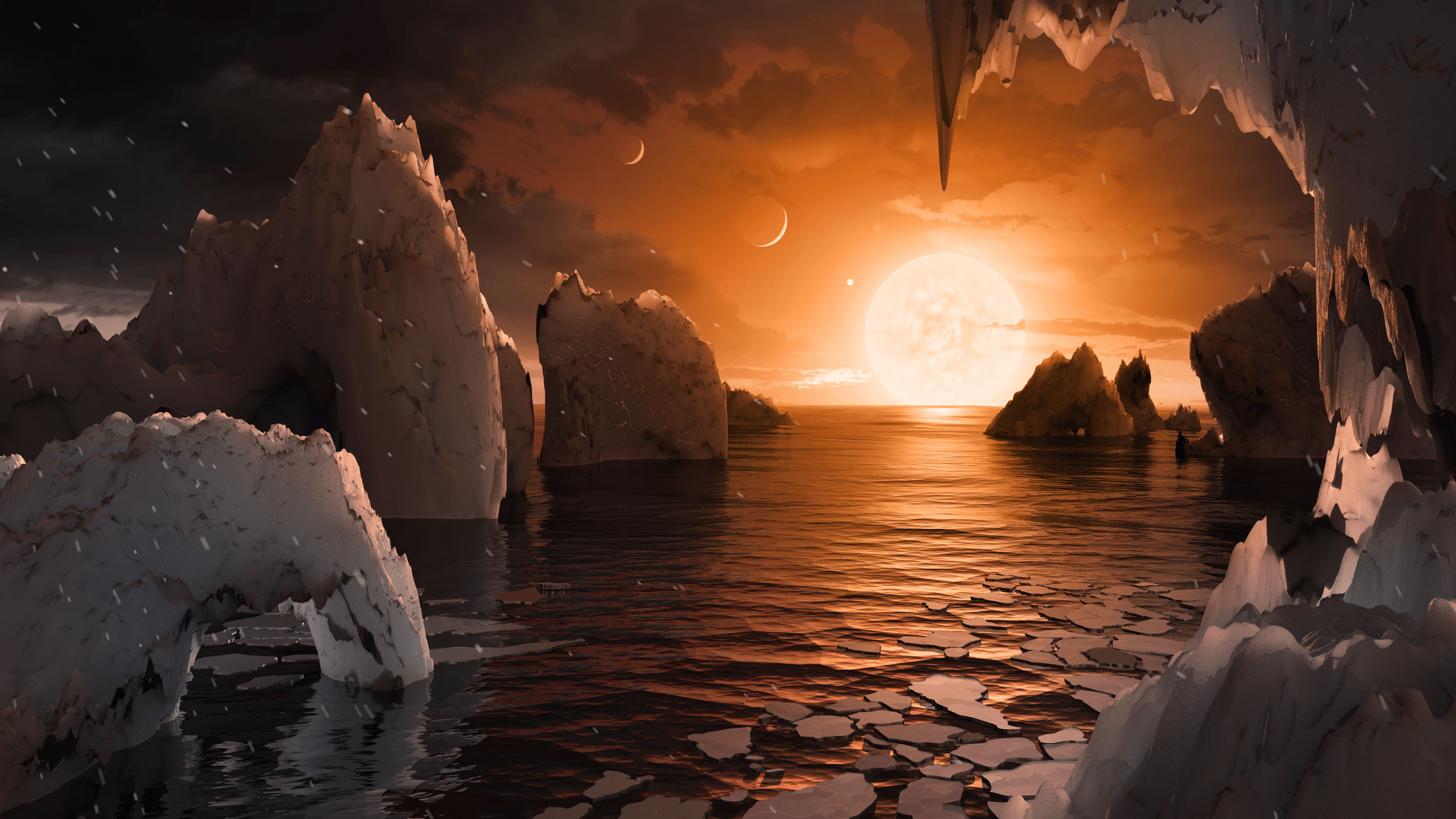

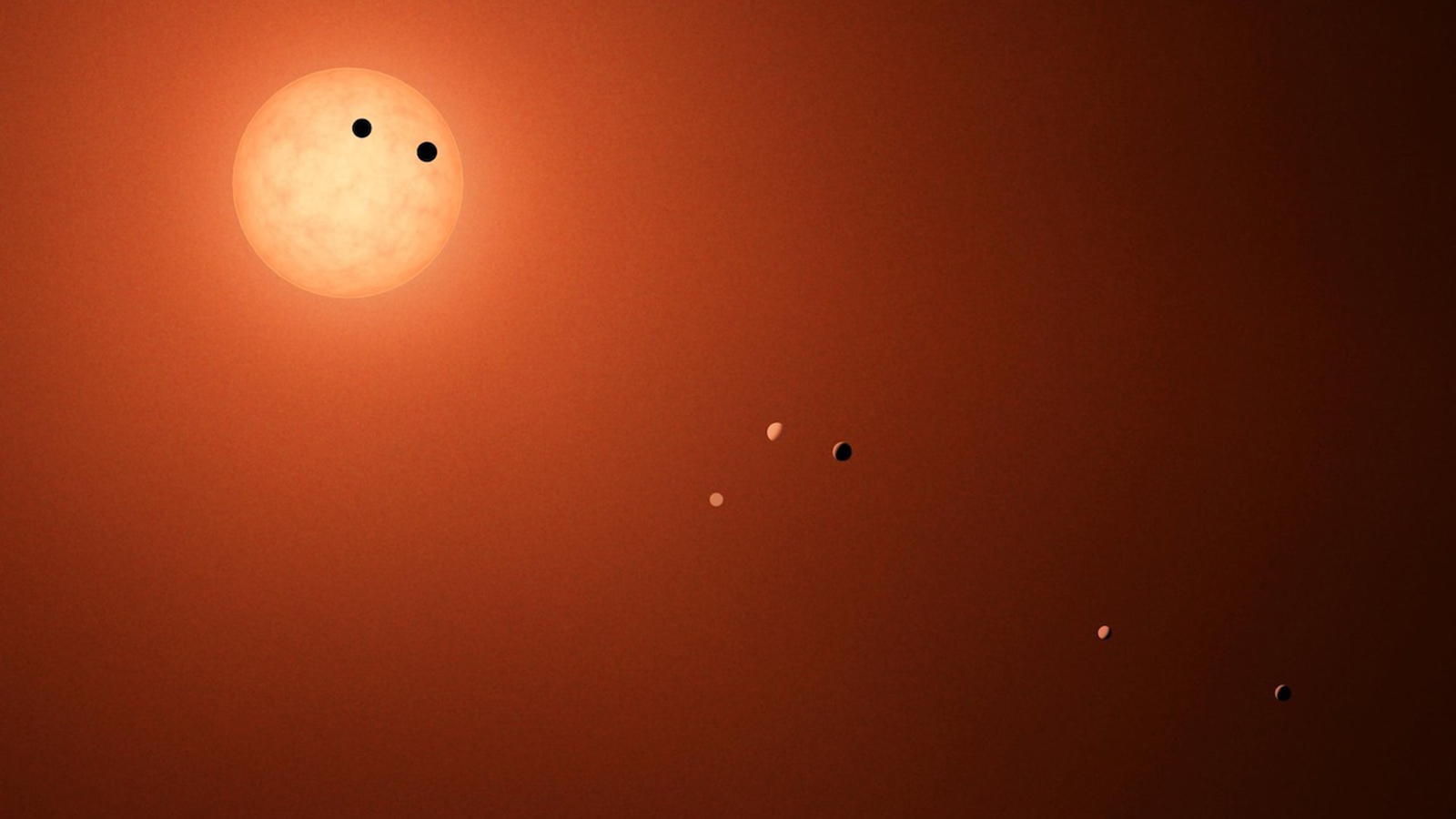

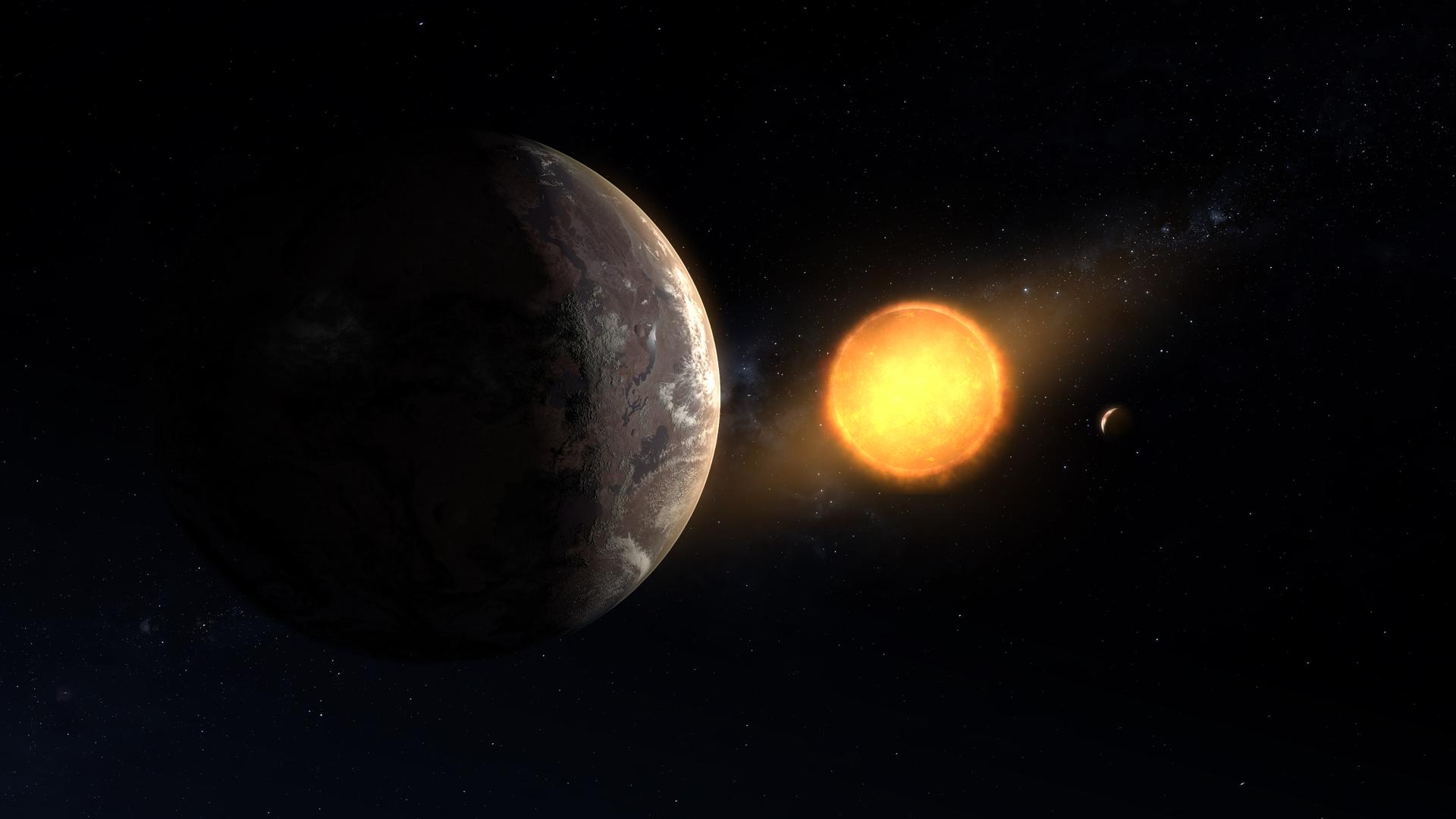

This is not your parents’ universe. You can take a planet-hopping vacation across the seven Earth-sized worlds of the system known as TRAPPIST-1, for instance, just 40 light-years away. A somewhat longer trip, around 200 light-years, will take you to Kepler-16b, a planet orbiting two stars. The two suns in its sky make it a real-life Tatooine, straight out of “Star Wars.”

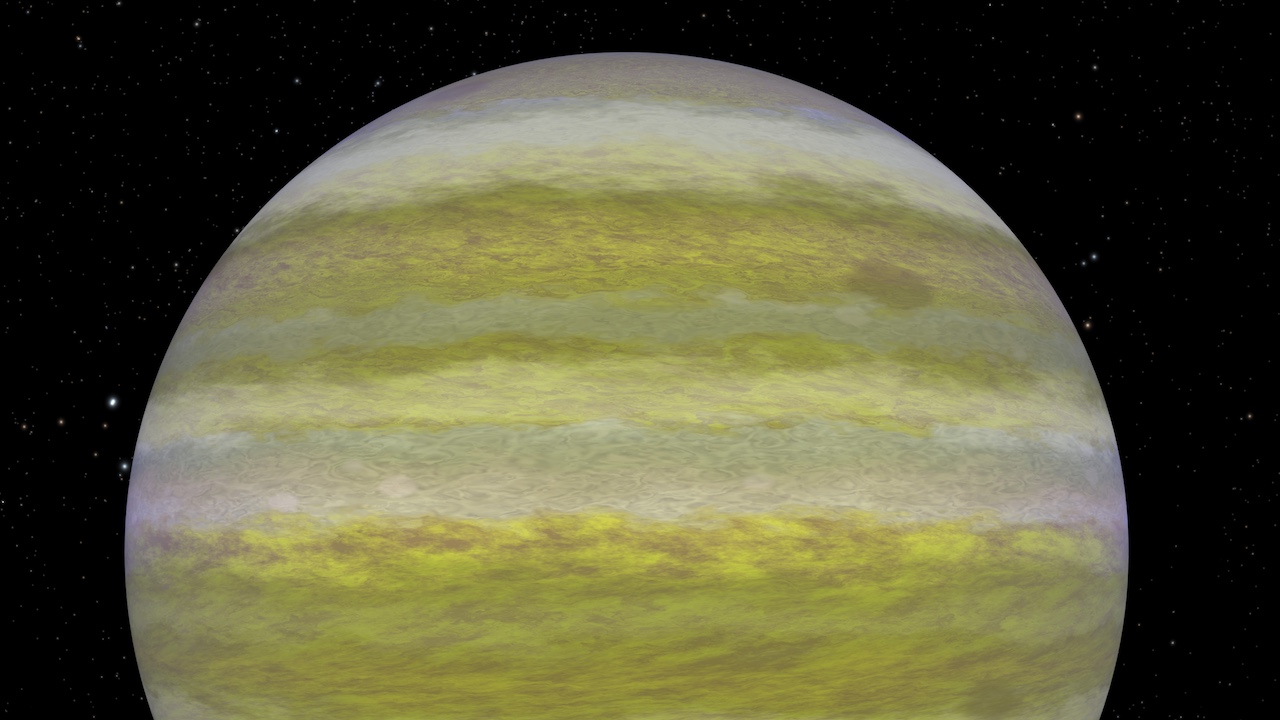

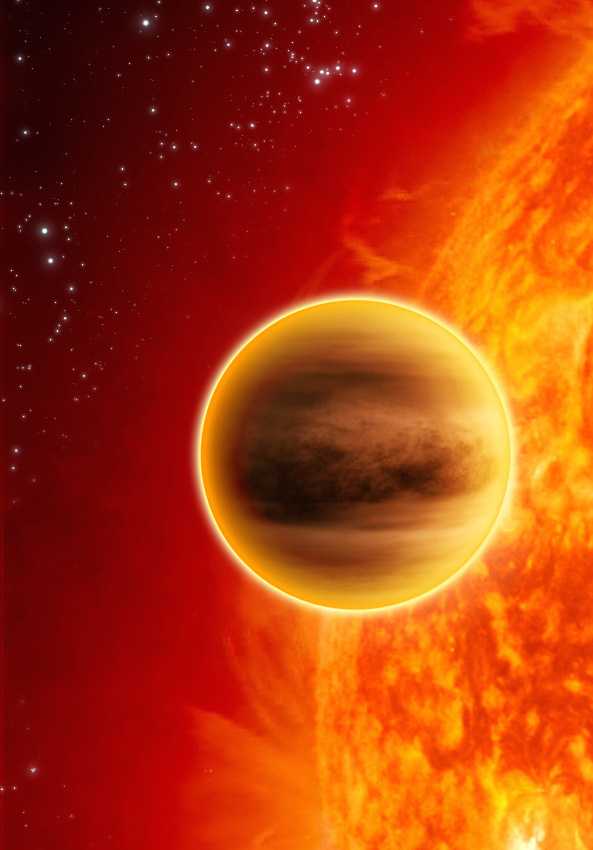

Or how about pitch-black WASP-12b, some 1,400 light-years away, orbiting its star so closely it’s being distorted into an egg shape as it is gradually pulled apart?

The count of confirmed exoplanets – planets around other stars – has passed 3,500 since 1995, when the detection of 51 Pegasi b, a roasting giant in a close orbit around a sun-like star, rang in the era of fast-paced exoplanet discovery. Dozens, then hundreds, then thousands began to jump out of telescope data.

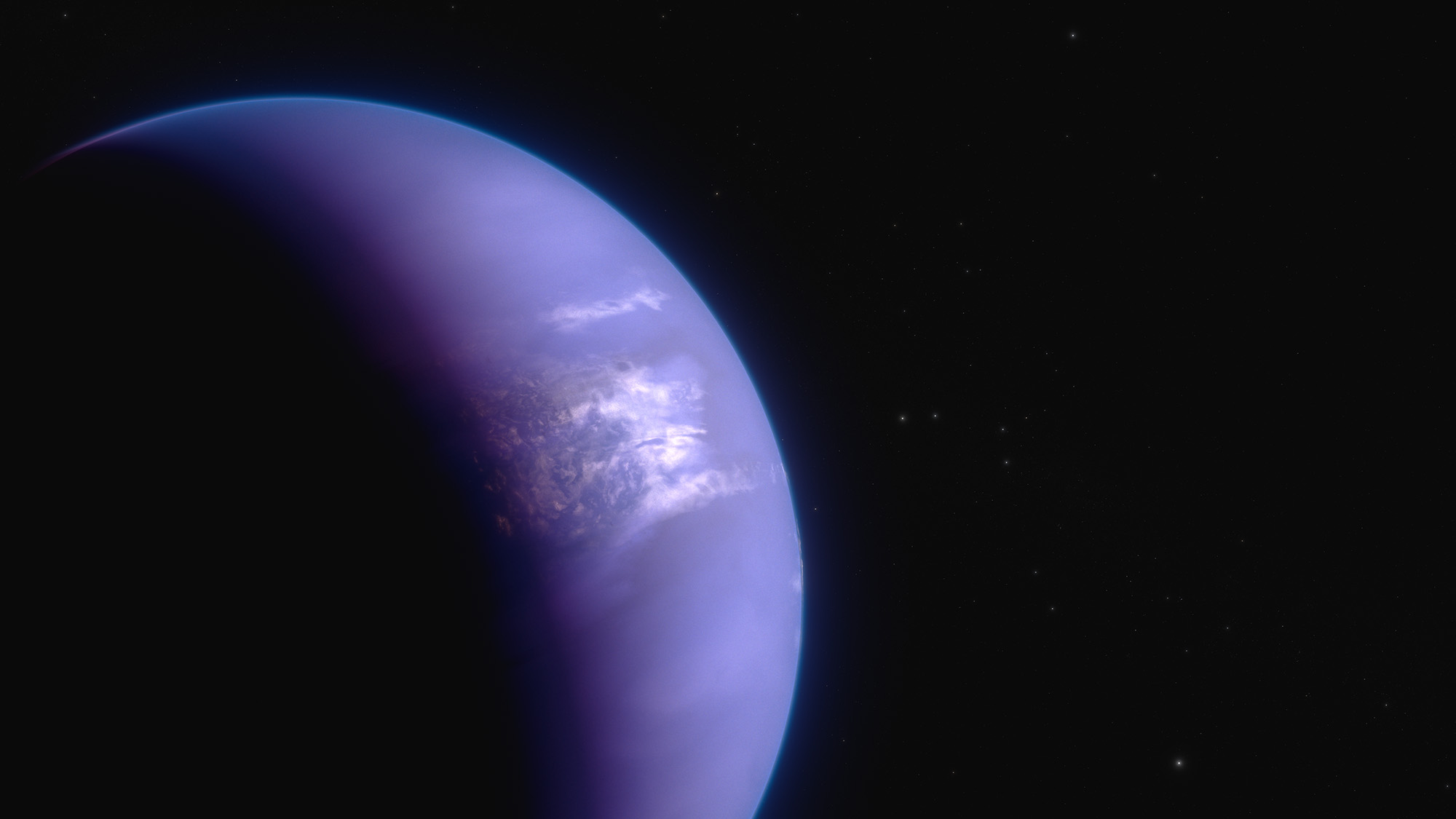

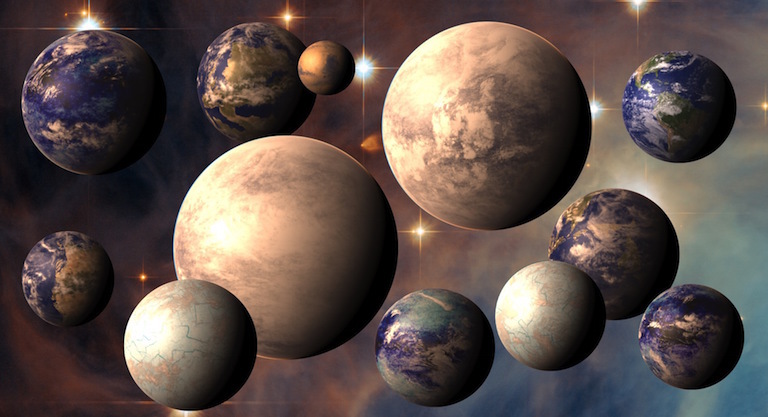

The Kepler space telescope reeled in the largest haul, providing a census of planet types and sizes. A planet as light as Styrofoam, another that could be raining glass. Earth-sized worlds by the bushel, but also oddly sized “super Earths” and “sub-Neptunes,” planets larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. These are the most common types of planets, though we know next to nothing about them: In our solar system they are conspicuously absent.

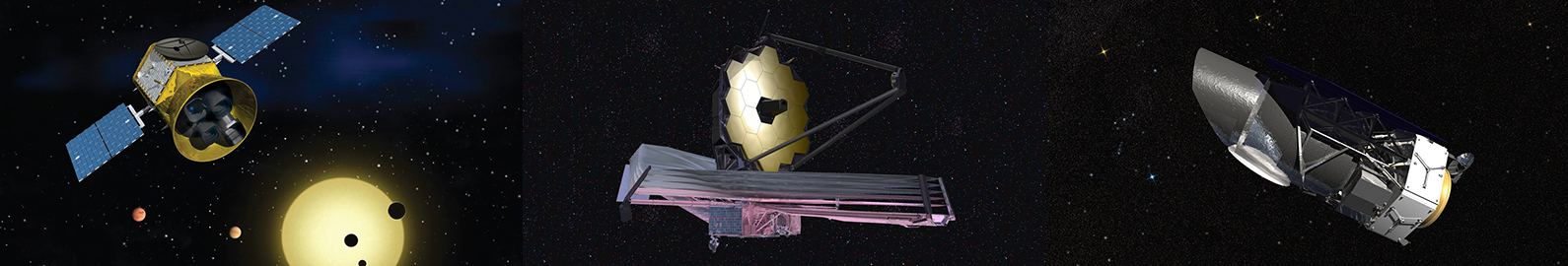

Reaction wheel failures ended the Kepler telescope’s primary mission in 2013 after four years of exoplanet observation. Some clever commands from ground-based engineers allowed it to continue functioning as K2, an extended mission mapping new star fields that lie within the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun. Its observation times are now shorter, but its ability to discover new exoplanets remains intact.

The K2 mission is, in fact, preparing the way ahead for two new, state-of-the-art planet hunters to be launched in the next two years. The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the James Webb Space Telescope will take their cues from K2, which is identifying interesting exoplanets that the new kids on the block can investigate in greater depth. The Webb telescope will capture the light from some of these planets, with the goal of determining which gases are present in their atmospheres.

All these worlds are yours. . .

Arthur C. Clarke

"2010: ODYSSEY TWO"

The age of direct imaging – actual pictures – of exoplanets is upon us, even if the first images are no bigger than a pixel. And the techniques pioneered by the Webb telescope could one day allow us to identify oxygen, carbon dioxide and methane in the skies of some far-off, blue and white marble. In other words, signs of life – and just maybe, another Earth-like planet.

For now we can take these journeys to exotic exoplanets only in our imaginations, though helped along by the visions of space artists. Their visualizations, based on known data, are so sharp they look like photographs. Using exoplanet virtual reality and your cell phone, you can stand on the surface of an orange-tinted world, and look back toward Earth through its alien skies.

Welcome to our new exoplanet blog, part of NASA’s Exoplanet Exploration program. Hitch a ride with us as we take interstellar tours, discover new planets, and press ahead in the search for life. A brand-new universe is waiting.