NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope has detected light emanating from a "super-Earth" planet beyond our solar system for the first time.

From the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

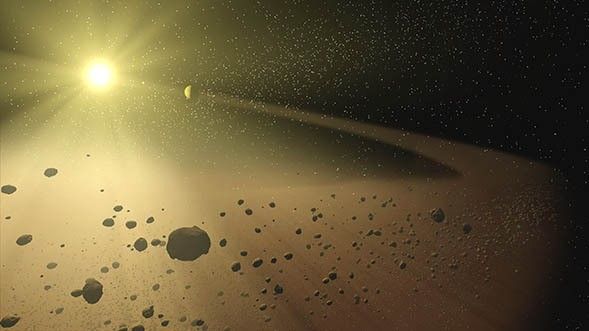

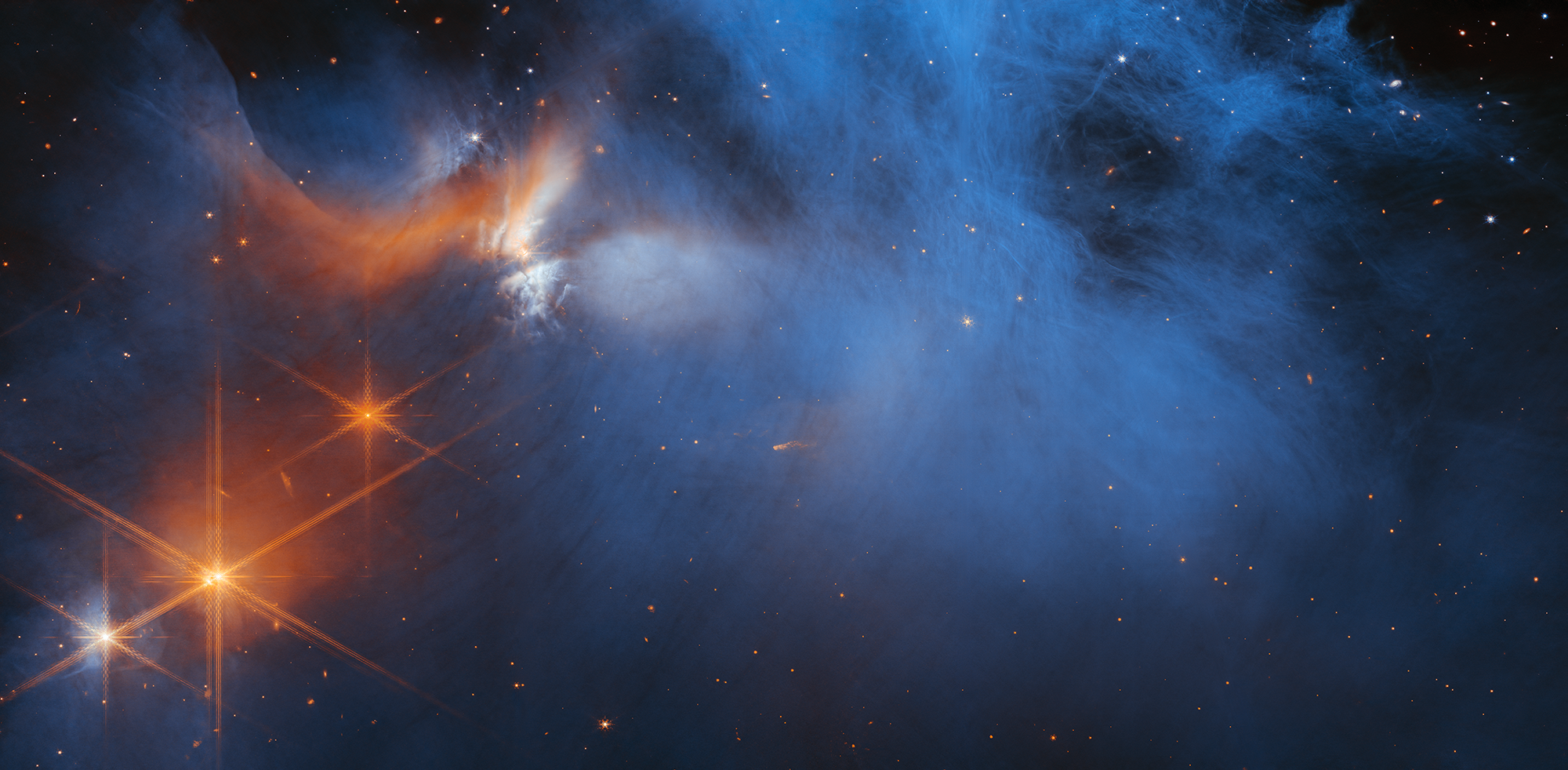

Planets are formed in disks of gas and dust around nascent stars. Now, combined observations with the compound telescope ALMA and the Herschel Space Observatory have produced a rare view of a planetary construction site in an intermediate state of evolution: Contrary to expectations, the disk around the star HD 21997 appears to contain both primordial gas left over from the formation of the star itself and dust that appears to have been produced in collisions between planetesimals – small rocks that are the building blocks for the much larger planets. This is the first direct observation of such a "hybrid disk", and likely to require a revision of current models of planet formation.

When a star similar to our Sun is born, it is surrounded by a disk of dust and gas. Within that disk, the star's planetary system begins to form: The dust grains stick together to build larger, solid, kilometer-sized bodies known as planetesimals. Those either survive in the form of asteroids and comets, or clump together further to form solid planets like our Earth, or the cores of giant gas planets.

Current models of planet formation predict that, as a star reaches the planetesimal stage, the original gas should quickly be depleted. Some of the gas falls into the star, some is caught up by what will later become giant gas planets like Jupiter, and the rest is dispersed into space, driven by the young star's intense radiation. After 10 million years or so, all the original gas should be gone.

But now a team of astronomers from the Netherlands, Hungary, Germany, and the US has found what appears to be a rare hybrid disk, which contains plenty of original gas, but also dust produced much later in the collision of planetesimals. As such, it qualifies as a link between an early and a late phase of disk evolution: the primordial disk and a later debris phase.

The astronomers used both ESA's Herschel Space Observatory and the compound telescope ALMA in Chile to study the disk around the star HD 21997, which lies in the Southern constellation Fornax, at a distance of 235 light-years from Earth. HD 21997 has 1.8 times the mass of our Sun and is around 30 million years old.

The Herschel and ALMA observations show a broad dust ring surrounding the star at distances between about 55 and 150 astronomical units (one astronomical unit is the average Earth-Sun distance). But the ALMA observations also show a gas ring. Surprisingly, the two do not coincide: "The gas ring starts closer to the central star than the dust," explains Ágnes Kóspál from ESA, principal investigator of the ALMA proposal. "If the dust and the gas had been produced by the same physical mechanism, namely by the erosion of planetesimals, we would have expected them to be at the same location. This is clearly not the case in the inner disk."

Attila Moór from Konkoly Observatory adds: "Our observations also showed that previous studies had grossly underestimated the amount of gas present in the disk. Using carbon monoxide as a tracer molecule, we find that the total gas mass is likely to amount to between 30 and 60 times the mass of the Earth." That value is another indication that the gas disk is made of primordial material – gas set free in collisions between planetesimals could never explain this substantial quantity.

Thomas Henning from the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy says: "The presence of primordial gas around the 30 million-year-old star HD 21997 is puzzling. Both model predictions and previous observations show that the gas in this kind of disk around a young star should be depleted within about 10 million years."

The team is currently working on finding more systems like HD 21997 for further studies of hybrid disks, and to find out how they fit within the current paradigm of planet formation – or the ways in which the models need to be changed.